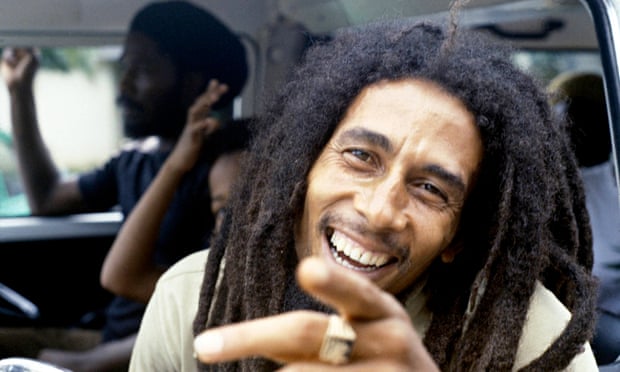

“Me no really say no bad things about no one, cause me have a full heart,”

Bob Marley once told me. “That is a sign of being an ignorant and undisciplined

human being. Me prefer just to understand the situation and suss it out and say

what is right and what is wrong.”

Confident in taking a stand, Bob Marley was not afraid to sing with moral

authority. As events echoing the struggles he took part in and sang about take

place around the world, I often find myself wondering: what would Bob have made

of this if he were alive to celebrate his 70th birthday? What songs might he

have written? Except that, usually, he already has.

As the repeated cop killings of black males across US prompt multiracial

“Black Lives Matter” demonstrations, there’s No Woman, No Cry and Johnny Was a

Good Man; when brutality cloaked as religious extremism strikes terror, Bob

sings, in We and Dem: “Me no know how we and them gonna work it out.” As the

Arctic melts and African lakes dry up, we all yearn for the “natural mystic/

blowing through the air”, and agree that the system of what Rastafarians call

“Babylon” – rapacious capitalism or a repressive regime – is indeed “a vampire,

sucking the blood of the sufferer”. Yet today, Bob Marley often appears as

remote a figure to young music-lovers as Leadbelly was to me back then, a

compelling but distant figure.

I teach a course at New York University called Marley and Post-Colonial

Music, and when you teach about people you actually knew, surreal moments occur.

Among the oddest? Seeing Saturday Night Live joke about my class on TV. “And in

a cruel twist,” deadpanned Seth Myers, “the NYU Bob Marley class is only being

offered at 8am.” The funny thing was, I really didn’t get the joke. (Neither did

my students, who plaintively emailed: “Do we really start so early?”) That’s

because the punchline depended on the idea that Marley was more notable for

marijuana than music, and implied that his fans must, by definition, be lazy

slackers. Yet not only were my students top rate, the Bob Marley I knew was

quite different. For him, ganja was a spur, a tool for a work ethic that was

impeccable, unceasing, even relentless. The in-house joke about Bob was “first

on the tour bus, last to leave the studio”. It was part of his leadership. But

that is often not how he is perceived, certainly in the US.

The music editor

of a popular US website recently told me of programmers at a midwestern college

radio station who scoffed at him for wanting to play Marley; that was apparently

an indicator of flakiness. He’s become the symbol of a spring break, ultra-amped

THC vape fever.

And when he does get played on the radio now, it’s the mellow songs, not the

angry songs, that get heard – the ones that have been compiled on albums such as

Legend, leaving the grittier material to collections such as Kingston 12. When

my class studied Exodus, and its sequencing, with the confrontational songs of

side one and the sunlit uplands of side two, they realised that though they all

knew the cheery love tunes, none of them had heard the songs of struggle, and

that applied to all Bob’s catalogue. Yet I remember his wry smile and tone of

mild protest as he asked “How long must I sing the same song?” when he was

criticised for following Exodus with the soft, sweet Kaya.

“If I had more men behind me, I would just be more militant!” he insisted.

And yet Bob was also happy to be making a new point. He didn’t want to be seen

only as a soldier, because “you have to think of a woman sometimes, and sing

something like Turn the Lights Down Low”. He couldn’t have anticipated that one

day the fighter would have been transformed in the popular imagination into a

lover and feelgood party dude. But as Bob said about his music: “What I like

about it is the way it progress.”

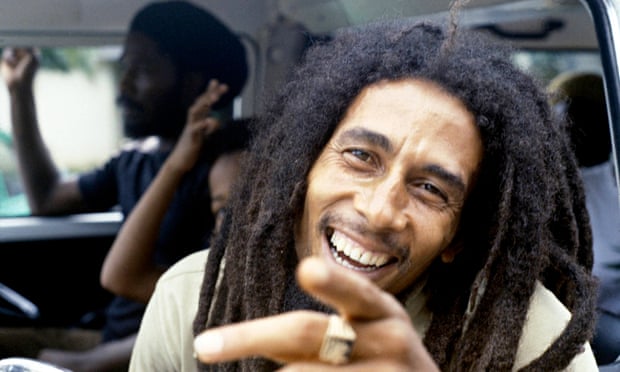

I am often asked if Bob Marley really meant all that righteous stuff. He did.

He was not infallible, but he tried to live up to his ideals, and he was

sincere. He once said to me: “The truth is the truth, you know. Sometimes you

have to just sacrifice. I mean, you can’t always hide, you have to talk the

truth. If a guy want to come hurt you for the truth – then, I mean, at least you

said the truth.”

Some of these exchanges with Bob occurred in 1976, at a pivotal moment in his

life. The previous year, I had been his PR at Island Records for seven months,

part of the team that helped break him in the UK with No Woman, No Cry. Then I

started writing frequently about him, on the road and at home. On one

assignment, Bob invited me to crash at his ample colonial home on Kingston’s

Hope Road, which was quite a commune, with an ever-revolving cast.

The conversations we had in those days, some of which I taped, were freighted

with a heavy subtext, immediate in a way I could scarcely have understood. Once

he said: “Jamaica is a funny place, mon. People love you so much, dem want to

kill you.” I took it to be an exaggeration. In the studio, he looked anxious

while recording one of his sunniest songs, Smile Jamaica. He told me: “Jamaicans

have to smile. People are too vex.” Late at night, he strummed a guitar in the

yard at Hope Road, composing the words that would appear on Guiltiness, about

big fish who always try to eat up small fish. Ruthless, self-interested

predators who would, Bob predicted, “do anything, to materialise their every

wish”.

Sure enough, the day after I left Hope Road for London, four politically

motivated gunmen broke into the Hope Road haven, shooting Bob, his wife Rita and

manager Don Taylor, and escaped. Bob and the Wailers went into exile for a year

and a half.

While I was researching The Book of Exodus, my book about Bob, the wife of

one of the dons – the gangleaders – who had grown to become a pacifist Rasta,

revealed that her husband had discovered the plot to shoot Bob, and called to

warn him. Thus even as Bob was hinting at vicious forces, he knew the plot

against him was ready. He knew the shooting was coming, even before the guns

barked. Just two days later, he went ahead and played the Smile Jamaica concert

designed to cheer and unite the people ahead of the December 1976 general

election, which was contested against a backdrop of vicious rivalries – between

the gangs and the two main political parties – with the dons and politicians

alike all seeing Bob as a figure they wanted on their side. Onstage on 5

December, Bob was still bandaged, and had a bullet in his arm that would remain

there to the grave; removing it would have put his guitar playing at risk. So he

well understood the price you can pay for taking a political stand, and he

carried on anyway. That’s courage.

Bob had a pragmatic, some might say cynical worldview. When the 1976 Notting

Hill Carnival riots rampaged on my old street, Ladbroke Grove, I happened to be

in Kingston talking to him. Breathlessly updating him on the plans to ban

Carnival, I pushed for his response. His thoughtful reply could equally apply to

today’s larger scale conflicts: “Well, we can’t really solve those problems,

because the people who start the problem know why dem do it. Them thing yah is a

plan because people must be getting too revolutionary, or they know too much

things. Something a gwaan.” He never lost sight of what it fundamentally meant

to be a Jamaican: “It’s fact that we come from the shores of Africa as slaves.

It’s really fact. So all the money and power them people have is just to keep we

in slavery still. And when you talk like that,” he continued, with a special

scorn, “them say you a talk about politics. They can talk about whatever, but as

far as the way me see it is – disobey them and die. Obey and die, too, because

if you obey them, you goin’ dead.”

A musician who laid his life on the line for his beliefs, expressed in songs

a child could hum? The story sounds almost quaint today. Now that musicians no

longer turn to protest as they once did, what does the message of Bob Marley

mean?

Throughout his life, Bob was an artist/entrepreneur who sought to control his

musical production. Having been royally ripped off by successive producers in

the early days, Marley was prepared, near the end of his life, to make a deal

with a multinational to fund his Tuff Gong label. It would have been a

collective for the many Jamaican musicians he esteemed. But his musical legacy

is now in the hands of a different generation. The post-mortem marketing of

Marley has been phenomenally successful, and his estate is one of the most

lucrative of any musician.

For several years after his death intestate, his One Love image was mocked by

a string of lawsuits, some between factions within the Marley family, some

involving the Wailers. (Disclosure: I was a witness for the Wailers band in one

such case.) Famously, amid the chaos of Bob’s failure to leave a will, his widow

Rita was badly advised by her lawyers; she forged Bob’s signature and was

removed from her role as estate executor. Being Bob for signature purposes was

apparently a longtime spousal habit, anyway – with a resigned sigh, Bob often

told friends: “Rita knows how to sign my name better than I do.” And on it went

from there. Among the results of the lawsuits is a curious conundrum for the

band that defined the spirit of brotherly Rasta I-nity. Two bands currently tour

as the Wailers, one featuring guitarist Al Anderton; the other, the iconic

bassman Aston “Family Man” Barrett, who was bankrupted by all the

litigation.

Meanwhile the post-Bob Marley empire grows apace. Its reach extends from

headphones to apparel, leisure reggae cruises and beyond.

In song, Marley predicted that not one of his seed would “sit on the sidewalk

and beg for bread”, and so they have not. He trained his children in music, and

several of them are successful artists today. The social constraints and family

rejection that Bob experienced, the conflicts that shaped him into the artist of

activism and empathy he became, were not his 11 children’s experience. He left

school in his early teens and was self-educated; they attended elite schools.

Bob’s eldest daughter, Cedella, a noted fashion designer, created the look for

the Jamaican Olympic team, writes children’s books and is producing upcoming

musical Marley. Ziggy and Rohan Marley are following in their farmer father’s

footsteps and launching eco-inflected produce lines. The young Marleys are

musically productive, too. With dancehall dons such as Buju Banton and Vybz

Kartel locked up, and audience fatigue with a diet of guns and slackness, the

Marley youth (loosely spearheaded by Damian, Stephen and Ziggy) are seen as

leaders of Jamaica’s progressive reggae renaissance, called the “roots revival”.

In collaborations such as Distant Relatives, with hip-hop artist Nas, Damian in

particular is fulfilling his father’s dream of bridging the Caribbean-American

diaspora.

Now the family is launching the Marley Natural brand of ganja. Marley Natural

has drawn praise and rebukes, but it is timely. Suddenly, ganja is starting to

be a legal commodity. The Marleys’ weed enterprise will create jobs in a sector

that many hope will transform the Jamaican economy, maybe even help break its

overdependence on tourism. If all goes well, it might help with the trickle-down

effect that Bob once advocated to me, based on the belief that the rich have a

duty to do something with their money. Speaking in a voice dripping with

sarcasm, he criticised men who “have $32m or more in the bank, and he wouldn’t

even have a factory so somebody can get a job or learn a trade, you know? They

just [want to hold their] money – and money is just like water in the sea.”

Critics of Marley Natural, like Dotun Adebayo in these pages, feel that

identifying Bob so thoroughly with weed trivialises his message. It’s ironic

that Bob’s great solace and inspiration, the sacred herb, which he took

seriously as a Rastafarian sacrament, has become part of a reductive perception

of Marley. Bob’s activist legacy is currently under threat of falling victim to

his status as a lifestyle choice.

Bob’s own values and perspective on how to live were clear. “You make sure

you do good,” he told me. “Although it hard fi always do good to everybody, you

do the best you can. Then God will give you pay, because it is so you get paid.

You might get material pay from man, but you get spiritual pay from God.”

And that’s the gap in the Marley legacy – the lack of some central

educational or cultural public endeavour bearing his name that is purely

altruistic. Various Marleys already have socially minded endeavours – notably

the Rita Marley Foundation in Ghana, supporting a village school and women’s

health. But many among those who love what Bob Marley represents long to see

some organised philanthropic attempt in Jamaica to manifest the altruism Bob

exemplified; he was known for handing cash out to lengthy lines of sufferers and

is estimated to have supported thousands in Jamaica, quite informally. Along

with sacrifice, charity is part of what made him a legend.

Maybe the concern is that whatever the Marley estate might do, it would never

be considered enough; that you can’t please everyone and those who feel rejected

might prove troublesome. The concern might be real. Maybe the forces arrayed

against peace-making cultural initiatives truly are prohibitive, despite the

estate’s wealth. Or maybe it’s a difficult dream worth pursuing. Certainly, such

a move would thrill the global Marley tribe and fulfill the mandate Bob stated

to me in 1976: “People have to share.”

One of the only times I saw Bob Marley angry was when he spoke about his

childhood in Trench Town. “When I live down in the ghetto, every day I have to

jump fence, police try and hold me, ya dig? Not for a week – for years! Years,

till we have to get free now. It’s either you a bad, bad man and they shoot you

down, or you make a move and show people improvement. It doesn’t have to be

material, but in freedom of thinking.”

Marley processed that beleaguered background into a spiritually led

philosophy of survival, rooted in knowing human nature, expressed through music.

Because, as he told me, “We grew up rough, but it’s life. Sometimes you have it

hard, sometimes you have it soft. Sometimes it is just problems, you know,

problems every day. The youth grow up with questions like, What is life? What is

my future? Because everybody a search.” Bob Marley found an answer in Rasta. On

the 70th anniversary of his birth in rural colonial Jamaica, millions still find

encouragement, comfort and hope in him.