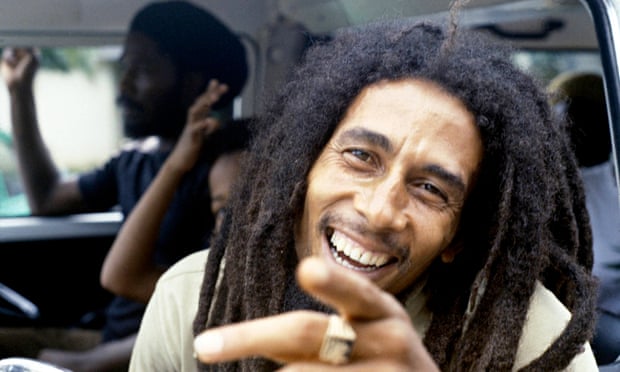

“Me no really say no bad things about no one, cause me have a full heart,” Bob Marley once told me. “That is a sign of being an ignorant and undisciplined human being. Me prefer just to understand the situation and suss it out and say what is right and what is wrong.”

Confident in taking a stand, Bob Marley was not afraid to sing with moral authority. As events echoing the struggles he took part in and sang about take place around the world, I often find myself wondering: what would Bob have made of this if he were alive to celebrate his 70th birthday? What songs might he have written? Except that, usually, he already has.

As the repeated cop killings of black males across US prompt multiracial “Black Lives Matter” demonstrations, there’s No Woman, No Cry and Johnny Was a Good Man; when brutality cloaked as religious extremism strikes terror, Bob sings, in We and Dem: “Me no know how we and them gonna work it out.” As the Arctic melts and African lakes dry up, we all yearn for the “natural mystic/ blowing through the air”, and agree that the system of what Rastafarians call “Babylon” – rapacious capitalism or a repressive regime – is indeed “a vampire, sucking the blood of the sufferer”. Yet today, Bob Marley often appears as remote a figure to young music-lovers as Leadbelly was to me back then, a compelling but distant figure.

I teach a course at New York University called Marley and Post-Colonial Music, and when you teach about people you actually knew, surreal moments occur. Among the oddest? Seeing Saturday Night Live joke about my class on TV. “And in a cruel twist,” deadpanned Seth Myers, “the NYU Bob Marley class is only being offered at 8am.” The funny thing was, I really didn’t get the joke. (Neither did my students, who plaintively emailed: “Do we really start so early?”) That’s because the punchline depended on the idea that Marley was more notable for marijuana than music, and implied that his fans must, by definition, be lazy slackers. Yet not only were my students top rate, the Bob Marley I knew was quite different. For him, ganja was a spur, a tool for a work ethic that was impeccable, unceasing, even relentless. The in-house joke about Bob was “first on the tour bus, last to leave the studio”. It was part of his leadership. But that is often not how he is perceived, certainly in the US.

The music editor of a popular US website recently told me of programmers at a midwestern college radio station who scoffed at him for wanting to play Marley; that was apparently an indicator of flakiness. He’s become the symbol of a spring break, ultra-amped THC vape fever.

And when he does get played on the radio now, it’s the mellow songs, not the angry songs, that get heard – the ones that have been compiled on albums such as Legend, leaving the grittier material to collections such as Kingston 12. When my class studied Exodus, and its sequencing, with the confrontational songs of side one and the sunlit uplands of side two, they realised that though they all knew the cheery love tunes, none of them had heard the songs of struggle, and that applied to all Bob’s catalogue. Yet I remember his wry smile and tone of mild protest as he asked “How long must I sing the same song?” when he was criticised for following Exodus with the soft, sweet Kaya.

“If I had more men behind me, I would just be more militant!” he insisted. And yet Bob was also happy to be making a new point. He didn’t want to be seen only as a soldier, because “you have to think of a woman sometimes, and sing something like Turn the Lights Down Low”. He couldn’t have anticipated that one day the fighter would have been transformed in the popular imagination into a lover and feelgood party dude. But as Bob said about his music: “What I like about it is the way it progress.”

I am often asked if Bob Marley really meant all that righteous stuff. He did. He was not infallible, but he tried to live up to his ideals, and he was sincere. He once said to me: “The truth is the truth, you know. Sometimes you have to just sacrifice. I mean, you can’t always hide, you have to talk the truth. If a guy want to come hurt you for the truth – then, I mean, at least you said the truth.”

Some of these exchanges with Bob occurred in 1976, at a pivotal moment in his life. The previous year, I had been his PR at Island Records for seven months, part of the team that helped break him in the UK with No Woman, No Cry. Then I started writing frequently about him, on the road and at home. On one assignment, Bob invited me to crash at his ample colonial home on Kingston’s Hope Road, which was quite a commune, with an ever-revolving cast.

The conversations we had in those days, some of which I taped, were freighted with a heavy subtext, immediate in a way I could scarcely have understood. Once he said: “Jamaica is a funny place, mon. People love you so much, dem want to kill you.” I took it to be an exaggeration. In the studio, he looked anxious while recording one of his sunniest songs, Smile Jamaica. He told me: “Jamaicans have to smile. People are too vex.” Late at night, he strummed a guitar in the yard at Hope Road, composing the words that would appear on Guiltiness, about big fish who always try to eat up small fish. Ruthless, self-interested predators who would, Bob predicted, “do anything, to materialise their every wish”.

Sure enough, the day after I left Hope Road for London, four politically motivated gunmen broke into the Hope Road haven, shooting Bob, his wife Rita and manager Don Taylor, and escaped. Bob and the Wailers went into exile for a year and a half.

While I was researching The Book of Exodus, my book about Bob, the wife of one of the dons – the gangleaders – who had grown to become a pacifist Rasta, revealed that her husband had discovered the plot to shoot Bob, and called to warn him. Thus even as Bob was hinting at vicious forces, he knew the plot against him was ready. He knew the shooting was coming, even before the guns barked. Just two days later, he went ahead and played the Smile Jamaica concert designed to cheer and unite the people ahead of the December 1976 general election, which was contested against a backdrop of vicious rivalries – between the gangs and the two main political parties – with the dons and politicians alike all seeing Bob as a figure they wanted on their side. Onstage on 5 December, Bob was still bandaged, and had a bullet in his arm that would remain there to the grave; removing it would have put his guitar playing at risk. So he well understood the price you can pay for taking a political stand, and he carried on anyway. That’s courage.

Bob had a pragmatic, some might say cynical worldview. When the 1976 Notting Hill Carnival riots rampaged on my old street, Ladbroke Grove, I happened to be in Kingston talking to him. Breathlessly updating him on the plans to ban Carnival, I pushed for his response. His thoughtful reply could equally apply to today’s larger scale conflicts: “Well, we can’t really solve those problems, because the people who start the problem know why dem do it. Them thing yah is a plan because people must be getting too revolutionary, or they know too much things. Something a gwaan.” He never lost sight of what it fundamentally meant to be a Jamaican: “It’s fact that we come from the shores of Africa as slaves. It’s really fact. So all the money and power them people have is just to keep we in slavery still. And when you talk like that,” he continued, with a special scorn, “them say you a talk about politics. They can talk about whatever, but as far as the way me see it is – disobey them and die. Obey and die, too, because if you obey them, you goin’ dead.”

A musician who laid his life on the line for his beliefs, expressed in songs a child could hum? The story sounds almost quaint today. Now that musicians no longer turn to protest as they once did, what does the message of Bob Marley mean?

Throughout his life, Bob was an artist/entrepreneur who sought to control his musical production. Having been royally ripped off by successive producers in the early days, Marley was prepared, near the end of his life, to make a deal with a multinational to fund his Tuff Gong label. It would have been a collective for the many Jamaican musicians he esteemed. But his musical legacy is now in the hands of a different generation. The post-mortem marketing of Marley has been phenomenally successful, and his estate is one of the most lucrative of any musician.

For several years after his death intestate, his One Love image was mocked by a string of lawsuits, some between factions within the Marley family, some involving the Wailers. (Disclosure: I was a witness for the Wailers band in one such case.) Famously, amid the chaos of Bob’s failure to leave a will, his widow Rita was badly advised by her lawyers; she forged Bob’s signature and was removed from her role as estate executor. Being Bob for signature purposes was apparently a longtime spousal habit, anyway – with a resigned sigh, Bob often told friends: “Rita knows how to sign my name better than I do.” And on it went from there. Among the results of the lawsuits is a curious conundrum for the band that defined the spirit of brotherly Rasta I-nity. Two bands currently tour as the Wailers, one featuring guitarist Al Anderton; the other, the iconic bassman Aston “Family Man” Barrett, who was bankrupted by all the litigation.

Meanwhile the post-Bob Marley empire grows apace. Its reach extends from headphones to apparel, leisure reggae cruises and beyond.

In song, Marley predicted that not one of his seed would “sit on the sidewalk and beg for bread”, and so they have not. He trained his children in music, and several of them are successful artists today. The social constraints and family rejection that Bob experienced, the conflicts that shaped him into the artist of activism and empathy he became, were not his 11 children’s experience. He left school in his early teens and was self-educated; they attended elite schools. Bob’s eldest daughter, Cedella, a noted fashion designer, created the look for the Jamaican Olympic team, writes children’s books and is producing upcoming musical Marley. Ziggy and Rohan Marley are following in their farmer father’s footsteps and launching eco-inflected produce lines. The young Marleys are musically productive, too. With dancehall dons such as Buju Banton and Vybz Kartel locked up, and audience fatigue with a diet of guns and slackness, the Marley youth (loosely spearheaded by Damian, Stephen and Ziggy) are seen as leaders of Jamaica’s progressive reggae renaissance, called the “roots revival”. In collaborations such as Distant Relatives, with hip-hop artist Nas, Damian in particular is fulfilling his father’s dream of bridging the Caribbean-American diaspora.

Now the family is launching the Marley Natural brand of ganja. Marley Natural has drawn praise and rebukes, but it is timely. Suddenly, ganja is starting to be a legal commodity. The Marleys’ weed enterprise will create jobs in a sector that many hope will transform the Jamaican economy, maybe even help break its overdependence on tourism. If all goes well, it might help with the trickle-down effect that Bob once advocated to me, based on the belief that the rich have a duty to do something with their money. Speaking in a voice dripping with sarcasm, he criticised men who “have $32m or more in the bank, and he wouldn’t even have a factory so somebody can get a job or learn a trade, you know? They just [want to hold their] money – and money is just like water in the sea.”

Critics of Marley Natural, like Dotun Adebayo in these pages, feel that identifying Bob so thoroughly with weed trivialises his message. It’s ironic that Bob’s great solace and inspiration, the sacred herb, which he took seriously as a Rastafarian sacrament, has become part of a reductive perception of Marley. Bob’s activist legacy is currently under threat of falling victim to his status as a lifestyle choice.

Bob’s own values and perspective on how to live were clear. “You make sure you do good,” he told me. “Although it hard fi always do good to everybody, you do the best you can. Then God will give you pay, because it is so you get paid. You might get material pay from man, but you get spiritual pay from God.”

And that’s the gap in the Marley legacy – the lack of some central educational or cultural public endeavour bearing his name that is purely altruistic. Various Marleys already have socially minded endeavours – notably the Rita Marley Foundation in Ghana, supporting a village school and women’s health. But many among those who love what Bob Marley represents long to see some organised philanthropic attempt in Jamaica to manifest the altruism Bob exemplified; he was known for handing cash out to lengthy lines of sufferers and is estimated to have supported thousands in Jamaica, quite informally. Along with sacrifice, charity is part of what made him a legend.

Maybe the concern is that whatever the Marley estate might do, it would never be considered enough; that you can’t please everyone and those who feel rejected might prove troublesome. The concern might be real. Maybe the forces arrayed against peace-making cultural initiatives truly are prohibitive, despite the estate’s wealth. Or maybe it’s a difficult dream worth pursuing. Certainly, such a move would thrill the global Marley tribe and fulfill the mandate Bob stated to me in 1976: “People have to share.”

One of the only times I saw Bob Marley angry was when he spoke about his childhood in Trench Town. “When I live down in the ghetto, every day I have to jump fence, police try and hold me, ya dig? Not for a week – for years! Years, till we have to get free now. It’s either you a bad, bad man and they shoot you down, or you make a move and show people improvement. It doesn’t have to be material, but in freedom of thinking.”

Marley processed that beleaguered background into a spiritually led philosophy of survival, rooted in knowing human nature, expressed through music. Because, as he told me, “We grew up rough, but it’s life. Sometimes you have it hard, sometimes you have it soft. Sometimes it is just problems, you know, problems every day. The youth grow up with questions like, What is life? What is my future? Because everybody a search.” Bob Marley found an answer in Rasta. On the 70th anniversary of his birth in rural colonial Jamaica, millions still find encouragement, comfort and hope in him.